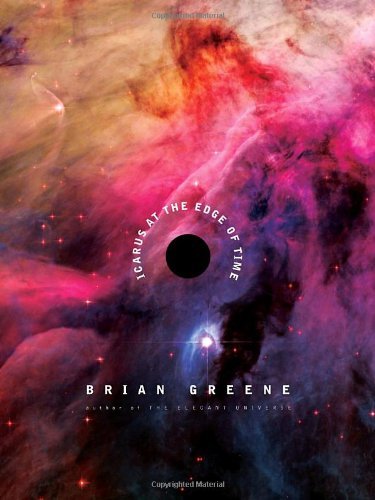

Product Description From one of America’s leading physicists--a moving and visually stunning futuristic reimagining of the Icarus fable. The starship Proxima is on a twenty-five-trillion mile journey. Icarus was born on the ship as was his father and his father’s father, but there will be two more generations before the Proxima reaches its destination. As the tale begins, the Proxima is making an emergency diversion to avoid a black hole. Icarus wants to get a closer look. Although his father explains that when something goes into a black hole it never comes out, Icarus is confident that he can journey to the black hole’s edge and still make it back. He sneaks one of the Runabout ships out of the docking station and sets off to explore the black hole on his own. The result is unexpected and startling. Icarus returns to find his world profoundly and forever transformed. In Icarus at the Edge of Time Brian Greene has given us a fable about fathers and sons, curiosity and wisdom, and the complexity of the universe as only a physicist of his range and lucidity could. Designed by Chip Kidd--with full-color images from the Hubble Space Telescope--it is destined to be a classic for all ages. An Interview with Author Brian Greene Q: After writing two big four-hundred-plus page bestselling books, what made you decide to write an illustrated book for all ages? A: There's an emotional side to science which the general public rarely experiences. When Einstein's calculations in 1916 showed that his new general theory of relativity could explain strange aspects of the planet Mercury's motion, he experienced--by his own description--heart palpitations. He'd revealed a fundamental cosmic truth and it filled him with awe and reverie. Yet, by contrast, in the public sphere science is still largely viewed as merely a cold body of knowledge. To many people, science is aloof, distant, abstract. I remember, some years back, reading a poem of Whitman’s about an astronomy student who grows tired and frustrated by his professor's teachings, and blissfully leaves the class to go outside, look skyward, and simply experience the wonderment of the star filled heavens. There are many for whom this poem would resonate. This highlights for me the need for people to connect with science in a new way--outside of the classroom and beyond the textbooks. My two previous books tried to make some heady ideas of modern physics widely available, and they did this through straightforward exposition. In Icarus At The Edge Of Time, my intention is to open a different kind of avenue onto science--a more visceral, more emotional side that a fictional narrative more readily accesses. Q: Where did the idea to re-imagine the Icarus legend (set in outer space and involving black holes!) come from? A: I recently told my two and a half year old son a bedtime story that involved space travelers moving near the speed of light. Within days he was telling his own animated stories of dinosaurs and monsters outrunning a new and wonderful concept--"the speed of dark." Which got me thinking. Storytelling is our most basic and powerful means of communication. We listen with a different kind of intensity--and open ourselves most fully--to a gripping tale. So why not allow some of science’s greatest wonders to be experienced not through pedagogy but through the force of narrative? Science in fiction, as opposed to science fiction. Scientific insights that are absorbed rather than studied. Icarus At The Edge Of Time is my first attempt to explore this terrain. Instead of a journey near the sun--a "light" star--Icarus heads to a black hole--a "dark" star. And then the wonders of Einstein's relativity kick in, warping the more familiar ending into a painful conclusion, to be sure, but perhaps one that's more hopeful than the original. Q: The story of Icarus is a cautionary tale, what do you think it has to say when applied (as it is here) to the nature of scientific exploration of the universe? A: Great scientists are great adventurers, boldly exploring unknown terrain--"anxiously searching" as Einstein once put it "for a truth one feels but cannot find, until final emergence into the light." Icarus's fearlessness fits this profile to a "T". But there's another side to scientific exploration. Scientific research has the capacity to reveal realms that turn the status quo on its head. And when this happens, we're often not prepared--as a society we're often not sufficiently mature--to take on the responsibility that such new realms can require. From nuclear knowledge to stem cells, from global climate change to cloning, science not only opens up new vistas but confronts us with profound challenges. In this new version of the Icarus tale, Icarus's unrestrained explorations take him, literally, to a startling new realm--one in which the universe as he knew it becomes forever beyond his reach. We can imagine him maturing into his new life and experience, but we also feel the wrenching pain of his being torn from his familiar reality--and from his family--and entering a completely new world--the very process of maturation we collectively navigate as science rewrites the rules of what's possible. Q: Who do you see as the audience for this book? A: The intended audience is broad. While I've found that science-enthusiasts get a big kick out of the story (it's not often that general relativity is the lynch pin in a narrative!), I wrote the story with two kinds of imaginary readers looking over my shoulder--adults who don't generally have much contact with science, and kids who love a short adventure story. Q: Since the writing of your last book you have become a father. How has fatherhood impacted you as a writer? A: I feel a stronger urge to go beyond a connection with readers that's purely intellectual. The intellectual side is critical of course. But I think you communicate far more effectively if you can engage the reader on multiple levels. I've always felt this way. But I now experience it everyday--all the time--with my son, and also my one-year-old daughter. Fatherhood has heightened my recognition that to communicate you need an emotional link. Q: Your passion for science and making it come alive for people of all ages is well known--as evidenced through your founding of The World Science Festival and also in a recent New York Times op-ed in which you wrote about "the powerful role science can play in giving life context and meaning," and stated, "It's the birthright of every child, it's a necessity for every adult, to look out on the world . . . and see that the wonder of the cosmos transcends everything that divides us." How do you feel about the way Science is taught in most schools today and what would be the biggest changes you would recommend? A: We need to get beyond the urge--however important--of merely teaching kids the results of science, the methods of science. We need to communicate the stories of science. If a kid thinks of science as a subject taught in a classroom, we've failed. Kids need to think of science as the greatest of adventure stories as we've sought to understand ourselves and the universe around us. Kids need to recognize that science is a perspective, a way of life--it's something you hold with you long, long after you leave the classroom. Q: What were some of the books that most inspired your passion for Science? A: When I was really young, it wasn't actually books that inspired me. It was great teachers. From my dad (a self-educated high-school drop-out) to a couple of public school teachers where I grew up in New York City, I was fortunate to be surrounded by people who knew how to nurture and excite a young mind. Q: So do you think anyone will ever actually find out what happens at the center of a black hole? A: Absolutely. But not by jumping in. Q: Is it a challenge, as a physicist and mathematician to write in a way that everyone understands? A: It is a challenge, but for me its both a useful and exciting one. I find that translating cutting-edge research into more familiar language forces me to strip away extraneous details and zero in on the core ideas. Often, this helps me to organize my own thoughts and has even suggested research directions. And it's exciting to see ideas that are close to my heart and those of other researchers in the field reach a wider audience. The questions we are tackling are universal, and everyone deserves the right to enjoy the progress we're making. Q: What are black holes and what do they tell us about the nature of universe? A: Black holes are regions of space filled with such intense gravity that anything which gets too close, even light, is unable to escape. Although Albert Einstein’s insights led to the idea of black holes, he remained skeptical about their existence. Yet, in the decades since, a wealth of astronomical observations have provided strong evidence that black holes not only exist in the cosmos, they’re commonplace. Black holes have a profound effect on time: their gravitational force pulls on time itself, slowing its rate of passage ever more as one gets ever nearer a black hole’s edge. Because of this, black holes provide for a specific kind of time travel. Were you to hover near the edge of a black hole, time for you would pass more slowly than for everyone else who remained far away. On returning to Earth you would thus find that hundreds or even thousands of years had elapsed, depending on the size of the black hole and how close you ventured to its edge. Scientists still haven’t figured out what happens at the very center of a black hole. Einstein’s mathematics breaks down and so provides no insight. Some scientists have suggested that a black hole’s center is where time comes to an end while others have proposed that it’s a portal to another universe. Finding the definitive answer is widely recognized as one of the great remaining challenges in our continuing quest to understand space,